Jan. 29, 2022

Misleading are the public relations efforts intending to make people feel good about weather dependent electricity from wind and solar “taking root” and “replacing” traditional continuous uninterruptable means of making electricity.

By Ronald Stein Ambassador for Energy & Infrastructure, Irvine, California

Tom Stacy Electricity System Analyst / Consultant, Ohio

Comparing nameplate ratings of various electrical generating powers sources is comparable to using IQ as the only or most appropriate measure of the value of an employee to the company he or she works for… If everyone had the same health level, skillset, and work ethic, it might suffice. But we don’t. And neither do different kinds of power plants.

For those of us who focus on the costs and benefits of various kinds of power plants within a grid system, it appears there has been an orchestrated effort through media, advertising, and public relations – even government agencies – to mislead the public about the value proposition of wind and solar.

One of the most glaring examples is the persistent use of “nameplate rating” (generating capacity) of breezes and sunshine as a benchmark of value and comparison. Nameplate rating itself is not a reflection of the contribution of energy or reliability to a grid system.

In the 20th century “nameplate rating” was a reasonable proxy for contribution to meeting peak demand whenever that peak may occur. Put another way, all prevalent power plant types could be turned on and run – up to their “nameplate rating” – whenever they were needed (aside from scheduled time for major maintenance or upon some small chance of unexpected breakdown) because they were able to manage their fuels.

For these tried-and-true technologies whose fuel availability is determined by human ingenuity and learning/adapting, it is common to de-rate nameplate rating by only about 10 to 15% to arrive at a “capacity value” or “system adequacy contribution” value (in reliable, on demand watts). This value for each power plant is added together across a system and the sum expected to meet maximum system demand (called peak load) with about ten to fifteen percent more as a “reserve margin” to avoid potential blackouts caused by unexpected generator outages or unexpected high demand.

The amount of reserve margin is a trade-off between the risk of black-outs (and other system reliability issues) and costs. So “right sizing” system “adequacy” is important to keeping electricity rates low because power plants cost far more to build and maintain than all the fuel they will ever consume over their lifespans. Accordingly, too many power plants are indeed too many because they are expensive to build, and therefore they rely on adequate revenue from their productivity to pay for themselves and produce a return on investment over several decades.

A 90 percent System Adequacy Contribution per watt of Nameplate Rating is fair and common across conventional types from coal to gas to nuclear. But wind and solar are different compared to technologies that have ‘Firm’ capacity. Their “fuels,” solar radiation and breezes, cannot be managed – i.e., consistently delivered and converted to electricity – and will never be. This is especially critical at the times demand is greatest. Therefore, they do not significantly replace the most expensive component of the cost of electricity: dispatchable power plants. Instead, they sap market share, gross margin percentages and revenue from the dependable fleet they can only pretend they can replace.

Just as problematic as renewables’ fundamental inability to generate at highest demand times is that these “intermittent fueled generators” often generate most when less power is needed by society, creating an undervalued market price for all electricity producers – sometimes lower than it costs them to generate (known as marginal cost), and far lower than the all-in cost to maintain system adequacy considering loan payments, payroll and other monthly expenses which must be met by all power plants.

For wind and solar “nameplate rating” is neither a measure of expected electricity generation over time nor their contribution to system reliability. Yet time and time again we see government entities, grid operators and especially news media spouting GENERATING CAPACITY (nameplate rating) in comparisons with conventional generating technologies.

Using nameplate capacity to compare technologies is misleading people into believing that weather dependent electricity can “replace” technologies that can manage their fuels when they cannot. This kind of reporting and public relations is, intentionally or not, biased toward intermittent generation. It’s sad when done by the media and public relations, and worse when done by a government agency.

However, with respect to cost comparison, US Department of Energy EIA states it clearly in their annual levelized cost of electricity reports, imploring:

“The duty cycle for intermittent renewable resources, wind and solar, is not operator controlled, but dependent on the weather or solar cycle (that is, sunrise/sunset)..(and so) their levelized costs are not directly comparable to those for other technologies..” ……………………………..

PJM, the largest wholesale electricity market operator in the world seems to agree in this statement describing the priorities in their most recent renewables transition study: “Correctly calculating the capacity contribution of generators is essential: A system with increased variable resources will require new approaches to adequately assess the reliability value of each resource and the system overall.”

This speaks directly to the importance of accurate system adequacy contribution comparisons between different generating technologies as the headline metric of value – instead of nameplate rating.

The correct two metrics of comparison between intermittent and dispatchable power plants that should supersede the use of nameplate rating are:

1) system adequacy contribution (in MWs) and

2) annualized electric energy generation (in MWhs)

Unfortunately, as PJM indicates, the methods of estimating system adequacy contribution are also controversial. The most widely used metric is “the old approach”, or ELCC (effective load carrying capability). That metric would be helpful if all generating technologies were symbiotic and not parasitic. In other words, ELCC fails to consider that wind and solar readily depress the financial viability of the existing dispatchable fleet that renewables require to remain, and that ELCC uses as a basis for the calculation of the system adequacy contribution of the “parasitic” renewables! In essence the metric isn’t well suited for an energy mix where competitive technologies aren’t direct substitutes for each other. ELCC is subtly circular in its reasoning since renewables have become politically favored into deployment and undermine the financial solvency of dependable power plant investments.

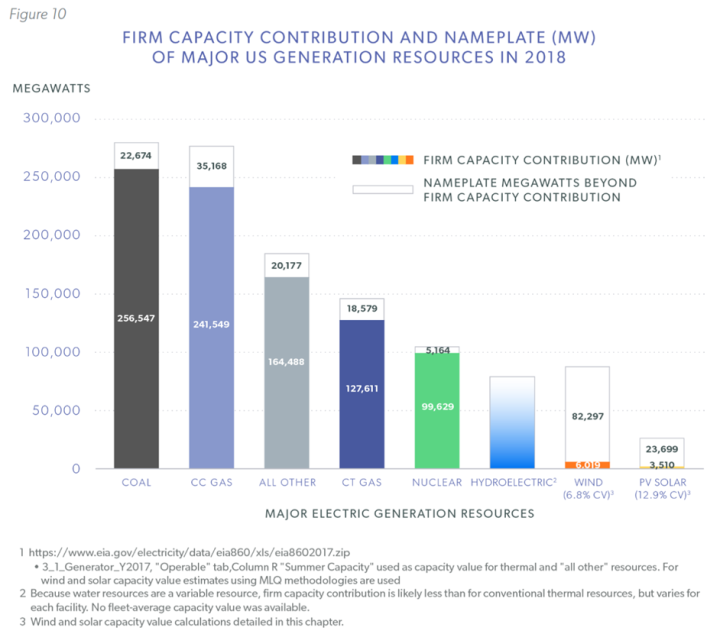

A better way of estimating system adequacy contribution looks at recent historical generating patterns of renewables in the context of the load patterns and amplitudes they might serve, independent of the existing generation mix. We favor one called “Mean of Lowest Quartile generation across peak load hours (MLQ) suggested by the market Monitor in its 2012 SOM report on MISO.

Realistically, by this metric, the following shows both nameplate capacity (outlined, not color-shaded) and system adequacy contribution (color-shaded) of the US electricity mix as of the end of 2018.

In using the wrong bases of comparison between power plant types, governments, market operators and image-obsessed companies are ignoring prudent economics and physics, placing the importance of the notion of a cleaner, self-sustaining world dependent on the weather for power ahead of real priorities like an affordable, abundant, and reliable electricity grid system, in accordance with FERC’s mission, to support human flourishing.

Renewables only “take root” because governments, market operators, utility regulators and misguided Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors – misguided only in that they do not account for how the Grid actually works, as discussed above – seek an unrealistic pace and impetus of “energy transition.” These push modern civilization toward reaching an economy like we had in the 1800’s and prior – the last time the world was “decarbonized”.

| Ronald Stein, P.E. Tom Stacy |

| Ambassador for Energy & Infrastructure Electricity System Economist |