Wired 1 January 2021

Methane from cattle accounts for a significant amount of global warming – startup Zelp has a comfortable and stylish solution

There are 1.6 billion cattle on Earth, and their burps and farts are becoming a big problem. Cows expel methane, a colourless and odourless gas which is approximately 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to warming the planet.

As a result, according to a recent report by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, the combined greenhouse gas emissions of America’s 13 largest dairy companies are equivalent to those of some major fossil fuel giants.

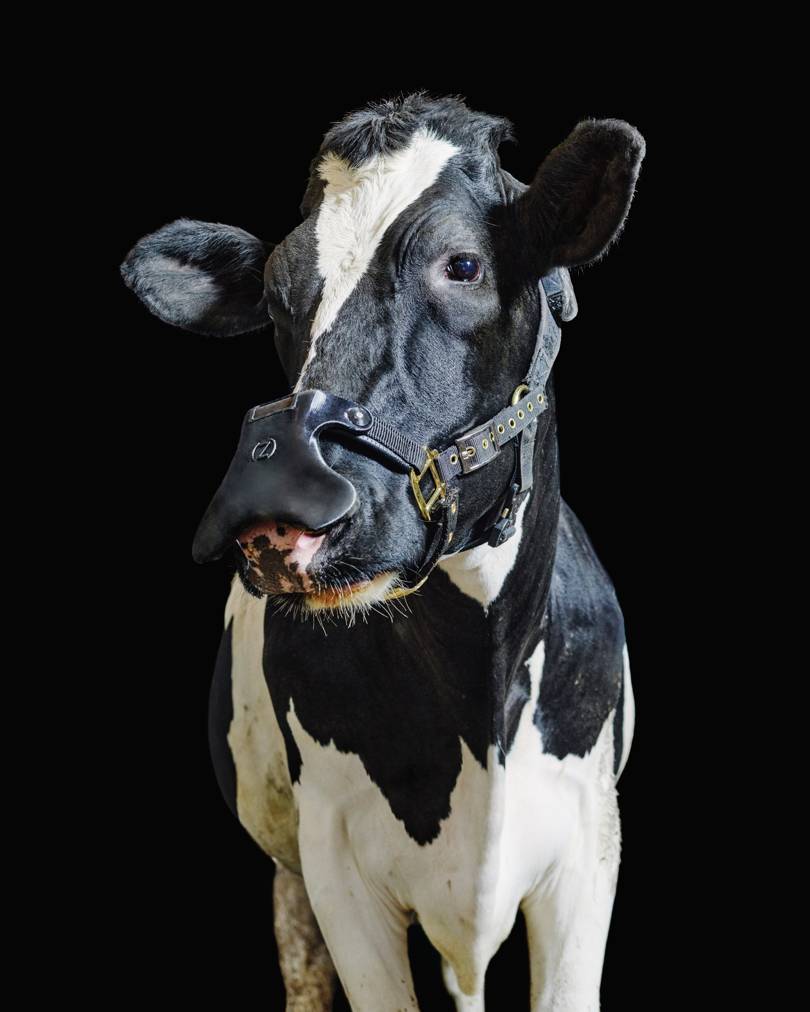

Zelp, a UK-based company, has developed a potential solution in the form of a burp-catching face mask for cows, designed to reduce methane emissions from cattle by 60 per cent. The firm was founded by brothers Francisco and Patricio Norris, whose family run a livestock farming business in Argentina. “We were aware that in every country, methane is one of the biggest contributions to global warming and we found that methane mitigation tools in agriculture are under-researched,” says Francisco. “There isn’t a lot of innovation occurring within the field.”

Generally, solutions to the livestock industry’s methane problem have come in the form of feed additives, which inhibit the production of the gas in the cattle’s stomachs by altering their digestive process.

Instead of changing the animals’ microbiology, Zelp allows animals to digest normal foods without this interference.

The mask fits comfortably on a cow’s head with a zip-tie-like mechanism allowing it to be adjusted to various cattle’s head sizes depending on the breed. It is applied to cattle after they are weaned, usually at 6-8 months of age, and sits next to the nostrils, allowing the tool to capture methane from their breathing, belches and burps. “Around 95 per cent of the cattle’s methane emissions come from their nostrils and mouths,” Norris explains. “The technology detects, captures and oxidises methane when it is exhaled by the animals.”

Zelp has conducted behavioural trials and observations with institutions in the UK and Argentina, including the Royal Veterinary College, which have indicated that the wearable has no impact on the animal’s behaviour and feeding.

Although reducing methane is at the forefront of the design, Zelp also measures feeding activity, cattle location and sexual receptivity in female cattle. With this information, the team can monitor individual animals and identify the early signs of disease, helping to improve welfare and reduce costs on farms. “All these parameters would combine in a different way,” says Norris. “For example, if you see methane production dropping but feed activity increasing, that could signal one thing. If you see methane production increasing and activity decreasing, that could signal a completely different thing.”

The data can also help determine how efficient or polluting a herd is – eventually, information could be collected across farms to understand methane emissions and cattle health at a regional and national level.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN predicts that beef and dairy consumption is going to rise by approximately 70 per cent in the next 30 years, and the team behind Zelp believe that the solution to ensuring climate action is implemented in time to meet global climate change goals lies in a collaborative approach. They hope their product will complement the development of alternative meat during this vital period – by capturing and transforming methane, one burp at a time.