Climate Etc by Judith Curry | Dec. 16, 2021

Politics versus the data versus communicating science.

On December 10 and 11, a catastrophic tornado outbreak slammed the Mississippi Valley, with catastrophic impacts particularly in Kentucky. One tornadic storm traveled more than 200 miles, and more than 100 people may have died. An excellent overview of the storm was written by Bob Henson [link]. Preliminary analysis indicates that the maximum tornado strength was EF4, with winds estimated as high as 190 mph.

Tornadoes and global warming

The links between tornadoes and climate change are more nuanced than for phenomena such as heat waves or extreme rainfall.

Fortunately, there is no sign that the number or intensity of the most violent tornadoes (EF3+) is increasing. However, tornadoes are becoming more tightly packed within outbreaks, and there are longer stretches in between, leading to more variability from quiet to violent periods and vice versa. Prior to Friday, the U.S. tornado death toll for 2021 was only 14, the third lowest in data going back to 1875. (The lowest on record was 10, set in 2018.)

There’s also been a distinct multi-decadal trend for recent outbreaks to shift into and east of the Mississippi Valley, particularly over the Mid-South, as opposed to the more traditional territory of the southern and central Great Plains.

As for seasonal timing, it’s never been impossible to get a violent tornado in December, even as far north as Illinois. At least two F5/EF5 tornadoes are on the record books for December: one in Vicksburg, Mississippi on Dec. 5, 1953, that killed 38 (the deadliest December tornado on record up to this year), and one on Dec. 18, 1957, that struck Sunfield, Illinois, as part of the state’s most severe outbreak on record so late in the year.

This December has been strikingly mild across most of the United States, and warm, moist surface air streamed into Friday’s tornadic storms, fueling their power. It’s not hard to imagine the springtime peak and the autumn second-season peak of tornado season edging closer to winter as greenhouse gases continue to warm our climate globally, nationally, and regionally. Such a shift in tornado timing has been difficult to confirm thus far, though.

What does the IPCC AR6 have to say about tornadoes and global warming?

“trends in tornadoes… associated w/ severe convective storms are not robustly detected”

“attribution of certain classes of extreme weather (eg, tornadoes) is beyond current modelling & theoretical capabilities”

“how tornadoes… will change is an open question”

Politics

President Joe Biden made these statements in an interview:

Q Mr. President, does this say anything to you about climate change? Is this — or do you conclude that these storms and the intensity has to do with climate change?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, all that I know is that the intensity of the weather across the board has some impact as a consequence of the warming of the planet and the climate change.

The specific impact on these specific storms, I can’t say at this point. I’m going to be asking the EPA and others to take a look at that. But the fact is that we all know everything is more intense when the climate is warming — everything. And, obviously, it has some impact here, but I can’t give you a — a quantitative read on that.

Here is what Michael Mann has to say [link]:

Meteorologist Michael Mann of Penn State told USA Today: “The latest science indicates that we can expect more of these huge (tornado) outbreaks because of human-caused climate change.”

In another interview [link]:

We speak to climate scientist Michael Mann about the role of climate change in the storms and climate denialism among Republican leaders. “Make no mistake, we have been seeing an increase in these massive tornado outbreaks that can be attributed to the warming of the planet,” says Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University.

And then to top it off, there is this tweet – data ‘denial’ at its ‘finest’:

The ‘deceptive’ graph comes from a plot that is on the NOAA website [link] through 2014, which was updated by AEI thought 2018. NOAA’s explainer of the data can be found [here].

The data

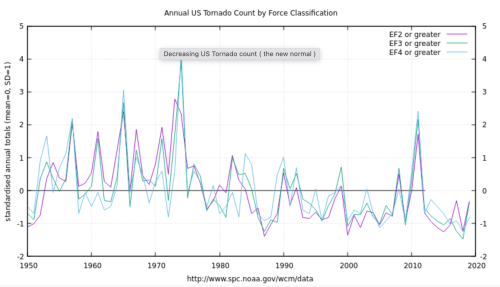

Chris Martz, an undergraduate meteorology student at Millersville University, provides the following plots of NOAA’s tornado record

Here are the plots of December tornadoes from NOAA data:

The US FEMA administrator says December tornadoes are the ‘new normal’ [link]. It seems that 1963 is the only year on record with no US tornadoes during December.

With regards to normalized U.S. damage from tornadoes, Roger Pielke Jr provides this graph [link]:

Greg Goodman’s analysis

Historical data of tornado events in USA is often dismissed as unreliable because of changes in observational techniques affecting reliability and consistency of reporting. IPCC SREX claims: “There is low confidence in observed trends in small spatial-scale phenomena such as tornadoes and hail because of data inhomogeneities and inadequacies in monitoring systems.”

One of the main factors in such inhomogeneity was the development and deployment of Doppler RADAR starting in the mid 1980s, though deployment is an ongoing process in the decades since. Other factors are the spread of urbanised areas into rural areas and facility of reporting by non technical persons due to hand held devices and ready access to global communications. RADAR observations record many smaller events which would not have been seen or recorded previously. Historically, many events were recorded by insurance claims when they affected property or crops and this meant many minor events would go unreported unless they caused injury or significant damage. However large, powerful events are unlikely to be missed.

Tornadoes are classed according to the Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF Scale). Examination of the available data from 1950 to end 2019 shows more powerful events ( classified EF2 or greater ) display consistent progression over time and it is just the lower magnitude EF0 and EF1 which are boosted in recent years by better, more comprehensive reporting.

Method

The archive of individual tornado events lists each event by date and provides several data such as location, force rating and fatalities. The number of events of each force rating in each calendar year were calculated, then each time series was standardised (subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation ) to see the relative progression of each category over time.

Analysis

After the strongest year in the record, 1975, there was a marked reduction in tornado activity in all categories. With the exception of a few lesser peaks, activity remained below average ever since. EF2, EF3 and EF4 categories all show very similar progression over time in both individual years of activity and long term trends. It is very unlikely that massive tornadoes would go unnoticed and unreported, so the similarity in the temporal evolution of each category indicates that reporting, down to EF2 is consistent over time. The data are coherent and self consistent between categories, which gives confidence that there are no major reporting induced biases present.

The period from 1950 – 1975 shows a steadily rising level of activity reaching a climax in 1975. After that there was a sudden and marked decline with no sign of a reversing increase since. All three categories are strikingly similar, which indicates there is no tendency towards a greater proportion of more power or less powerful storms over this period.

The post 1975 period marks the beginning of the late 20th century warming which IPCC has attributed mainly to anthropogenic effects ( AGW ). If there is a need to hypothesise a link between “global warming” and the frequency or intensity of tornadoes in USA, it would be that there have been less events in all major categories during this warming period. There has been no significant change in the distribution in storm severity as temperatures rise and recent warmer decades have seen notably less activity than the earlier post-WWII cooling period.

The ‘messaging’

Marshall Shepherd wrote a good article in Forbes entitled How Climate Messaging Spun Out Of Control During the Tornado Outbreaks.

The good news is that climate change is being discussed with greater vigor. The bad news is that some of that discussion is cringe-worthy. Recent tornado outbreaks sparked a frenzy of coverage about connections to climate change. In my view, some of the messaging spun out of control.

I reached out to Professor Allen for his thoughts on messaging in the aftermath of the December tornadoes. The Central Michigan University scholar told me, “There is a philosophical point where I think we have to be careful to know the limits of our expertise and capability when agreeing to interviews.” I am a scientist who receives media requests frequently. There are so many media outlets these days that content is at a premium and so are “talking heads.” Relative to the audience, I probably can speak to a range of weather, climate, and Earth science topics. Though my degrees are in meteorology, I get asked about wildfires, tsunamis, meteors, and other basic topics, and it is usually ok.

However, we all have limits. Allen goes on to say, “While we might be able to talk about other fields at a basic level, for most of the science (particularly regarding climate change), it is often the nuance which defines what we are able to say – and familiarity with the latest developments in the field tends to be where this is exposed most.” Such nuances can be even more challenging for an “expert” speaking without firm meteorological or climate science grounding.

Expert saturation is another problem. In the midst of events like the December tornado outbreak, journalists are seeking input from experts. Many of the experts become overwhelmed by the requests. It is a double-edged sword. Scholars like Trapp, Brooks, Gensini, and Allen have achieved a certain level of credibility and become “go to” sources. However, when the expert pool “saturates,” there can be a tendency to move to other options. Often, those options are mostly just fine. However, some choices end up being cringe-inducing. Professor Victor Gensini, an expert at Northern Illinois, told me the saturation thing is real. He has done over 50 interviews in the past week and referred 30 others. He wrote, “Honestly, I share a very similar sentiment to you….I think the real issues arise when ‘fringe field’ experts come in and try to apply their perspective and research to the question of the day.”

At the end of the day, there are multiple messages and messengers out there. This is not going to change. How can we deal with conflicting narratives in real-time, poor science grounding by some talking heads, or the saturation problem. I am not sure.